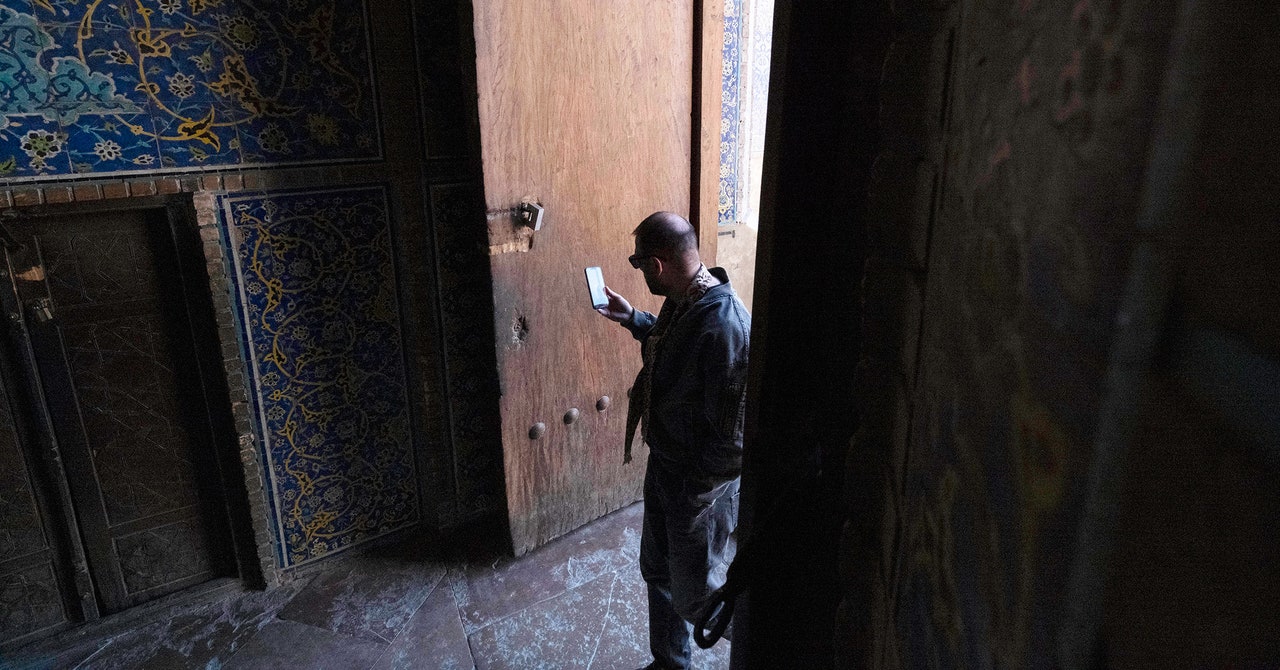

Alimardani reports that mobile data services in Iran are inconsistent, and many citizens are finding that virtual private networks (VPNs), used to bypass censorship, have ceased functioning. This disruption complicates communication efforts both for those within the country and for their families abroad. “Some family that left Tehran today were offline and disconnected from the internet and finally found some connectivity when they were 200 kilometers outside of Tehran in another province,” Alimardani explains, noting that his own connections, primarily using home broadband Wi-Fi, have also experienced instability.

In recent years, governments have increasingly resorted to cutting off internet access during crises, with 296 shutdowns reported last year alone by Access Now, a nonprofit monitoring internet rights, marking the highest number on record. Such actions are frequently associated with authoritarian regimes aiming to suppress dissent, restrict open communication during conflicts, or even curb cheating during exams.

Hanna Kreitem, director of internet technology and development at the Internet Society, emphasizes the critical importance of the internet during conflicts. “The internet is a lifeline; we have seen this in many places under conflict,” he says. Kreitem recounts that connectivity in Iran began to deteriorate noticeably on June 13, prompting concerns from individuals with family in the region. “People under fire use it to get news, request help, learn of safer areas, and communicate with loved ones. And for people outside to learn about what is going on and know about their loved ones.”

To curb internet access, countries implement various technical measures. Iran has sought to establish its own internet system, the National Information Network (NIN), which allows the government to impose different tiers of internet access, control censorship, and encourage the use of domestic applications that may lack robust privacy and security. Freedom House has rated Iran as “not free” regarding internet freedom, citing persistent shutdowns, rising costs, and efforts to push citizens toward the state-controlled internet.

Amir Rashidi, director of digital rights and security at the Miaan Group, highlights how recent shutdowns have spurred attempts to promote Iranian applications. “In a climate of fear, where people are simply trying to stay connected with loved ones, many are turning to these insecure platforms out of desperation,” he shared with WIRED, noting that the messaging app Bale has gained traction. “Since they are hosted on NIN, they will work even during shutdown,” he added.

According to Lukasz Olejnik, an independent consultant and visiting senior research fellow at King’s College London, Iran is not alone in imposing internet restrictions in the name of cybersecurity. Over the past decade, numerous countries, including Myanmar, India, Russia, and Belarus, have cited security concerns as justification for similar blackout measures.

“Internet shutdowns are largely ineffective against real-world state-level cyberattacks,” Olejnik states, explaining that military and critical infrastructure typically operate on separate networks, making them inaccessible via the public internet. He adds, “Professional cyber operations could use other means of access, albeit it could indeed make it difficult to command and control some of the deployed malware (if this was the case). What it would block primarily would be access to information for the society.”

Alimardani remarks that the rationale behind internet restrictions for purported cybersecurity reasons remains unclear. He asserts that the real objective may be to maintain control over the Iranian populace. “The official narrative from state news channels portrays a strong war against Israel and a path to victory,” he notes. “Free and open access to media would undermine this narrative, and at worst, could incite Iranians to revolt, further eroding the regime’s power.”